Introduction

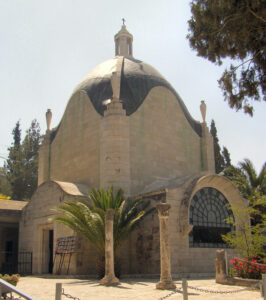

Show slide (Teardrop chapel) On the slope of the Mount of Olives, just outside Jerusalem, there is a chapel called Dominus Flevit, which means, “the Lord wept.” The chapel is constructed in the shape of a teardrop. It commemorates the story of Jesus entering Jerusalem as told in Luke 19, where we read, “as Jesus came near and saw the city, he wept over it, saying, “if you…had only recognized on this day the things that make for peace!” (Luke 19: 42).

Show slide (inside altar)

Inside the “teardrop chapel” there is an altar.

Show slide (hen and chicks mosaic)

On the front of the altar is a mosaic that depicts a large white hen, her wings spread wide to shelter seven chicks. This image is taken from Luke 13, when Jesus is warned that Herod wants to kill him (Luke 13: 31) Jesus laments over Jerusalem for its history of killing prophets, and then he says, “How often have I desired to gather your children together as a hen gathers her brood under her wings, and you were not willing!” (Luke 13: 34). Here Jesus calls on a comforting image used many times in the Psalms, of God as mother hen, sheltering Israel under her protective wings (see Psalm 17:8; 57:1; 61:4; 91:1-4 and Ruth 2:12).

Show slide (view of Jerusalem)

From this location on the Mount of Olives there is a spectacular view of the city of Jerusalem, across the Kidron Valley. Today the Dome of the Rock shines prominent.

Show slide (replica of first century Jerusalem)

This is a replica of first century Jerusalem. You can see how in Jesus’ day the Jewish temple dominates the foreground.

In both these stories Jesus, approaching Jerusalem, is overcome with emotion. He laments. He weeps.

Turn off slides.

Jesus Enacts a Parable

This Sunday we enter Holy Week. During the last five weeks of Lent we have been sticking close to Jesus, listening to his powerful parables as told in Luke 10-19. This section is called the “travel narrative” because Jesus has “turned his face toward Jerusalem” (Luke 9:51).

The stories in this part of Luke’s gospel (ch 10-19) are dramatic and intense. The themes are powerful, challenging, even troubling. There is a growing sense of urgency to Jesus’ teachings. He is trying to help his disciples “get” his message, and understand what it means to join his movement. Tensions build with the Pharisees. And for the disciples and crowds following Jesus, there is anticipation of an inevitable showdown between Jesus and the powers that be in Jerusalem. The “travel narrative” reaches a crescendo this week as Jesus rides into Jerusalem on a donkey (Luke 19:28-44). Is this the time for the Messiah to stand up against Roman oppressors and set the people free?

In this “travel” section of Luke we have studied several powerful parables: Lazarus and the Rich Man, The Good Samaritan, The Great Banquet and The Parables of Lost Things. But in this story Jesus is no longer telling a parable. He is the parable. He is enacting a parable, and like his other parables, it is rich with symbolism, and it has surprise elements and strong echoes from the prophetic writings. This is street theatre at its finest, and Jesus chooses his timing, his props and his movements with intention. It is “brilliantly planned prophetic actions” according to one writer (Jason Porterfield, Fight Like Jesus: How Jesus Waged Peace Throughout Holy Week, 34).

And so this past Wednesday evening at the bible study, we tried to imagine ourselves as a drama troupe, preparing to stage this story of Jesus riding into Jerusalem as a piece of theatre. We considered characters, setting, props, lighting, sound, timing and movement. We soon realized that there are strange signs that this is not a parade for a victorious holy warrior like the heroes of old. Let’s take a closer look.

The Characters

First of all, what is it with the donkey?! You would think it’s the main character! It takes up so much space in this story. Of course, Jesus is important too, but the donkey seems central. And why the foal of a donkey, one that has not yet been ridden? For those witnessing Jesus’ ride into Jerusalem, the donkey symbolizes something important (and Mike did a great job in the Children’s Time of exploring that).

It was accepted practice that when a king’s entourage traveled through an area they could procure things they needed from the locals. And so with little opposition, a local citizen releases his donkey’s foal to the disciples of Jesus, in response to the words, the Lord needs it (Luke 19:32). Further back in their history the people would remember the story of Solomon riding on a donkey to the place he was to be anointed king of Israel, to succeed his father David on the throne (1 Kings 1:33-34). They would remember the words of the prophet Zachariah, Rejoice greatly, O daughter Zion! Shout aloud, O daughter Jerusalem! See, your king comes to you; righteous and victorious is he, humble (gentle) and riding on a donkey, on a colt, the foal of a donkey (Zechariah 9:9). And they would remember what comes next in Zechariah’s prophetic words: He will take away the chariot from Ephraim, and the war horse from Jerusalem; and the battle bow will be broken. He will proclaim peace to the nations…from sea to sea (Zechariah 9:10).

The donkey is, surprisingly, a kingly image. But it is a peaceable, humble king who rides on a donkey. It stands in stark contrast to another image in their history of kings riding in on battle horses, with warlike intentions and nationalistic ambitions. So the donkey is an important prop in this story, or maybe we should elevate its status to supporting character!

The Props

While we are talking about props, notice that the disciples threw their cloaks on the donkey for Jesus to sit on, and people kept spreading their cloaks on the road in front of him (Luke 19:35-36). Even this action has “kingly” associations. In another story from the past, the army officers spread their cloaks on the bare steps in honour of Jehu when he was anointed king of Israel (2 Kings 9:13), showing their deference to the new king.

Speaking of props, we will need palm branches for this parade, right? But wait! Luke says nothing about branches. Matthew and Mark describe people in the crowd cutting leafy branches from the trees and fields to spread on the road. Only John describes them as palm branches. Palm branches were significant symbols of a time when Jewish fighters, called the Maccabees, liberated their people from the Greeks who ruled over them at the time. As Judas Maccabeus recaptured parts of Jerusalem, and rode, triumphant into the city, his followers waved palm branches. The Maccabees even minted their own coins, imprinted with palm trees. So we wondered if it is intentional that Luke leaves out any reference to palm branches, those politically loaded symbols of nationalistic pride. After all, Luke emphasizes Jesus as a peacemaker all through his gospel.

The Setting

Now, we also need to talk about the setting for this parable that Jesus is acting out. The timing and the place matter. Jesus made his way into Jerusalem on Sunday, the first day of the Passover Festival, on the tenth day of the Jewish month of Nisan. The day when every family selected its lamb for sacrifice, as God commanded to Moses in Exodus 12:3. This commemorates the day when God finally freed their people from slavery under the empire of Egypt. The sheep for the sacrifices in Jerusalem were supplied from Bethlehem, not far away, and brought into the city through the northeast gate, known as the Sheep’s Gate. Jesus’ route down the Mount of Olives joined the same path travelled by the sacrificial sheep, and he probably entered through the same gate.

Passover was the most sacred of all Jewish festivals. Pilgrims from all over crowded into the city. They remembered how God had liberated their people in the past. But they lived under Roman occupation, so Passover also served as a reminder that they were no longer free. With so many people dreaming of independence, Jerusalem could be a volatile place during Passover. There had been uprisings in the past. So the Roman governor of Judea, Pontius Pilate, made a point of riding into Jerusalem from the west, with his army: cavalry on horseback, foot soldiers with armor, helmets, weapons and banners. Pilate was sending a clear message: resistance is futile; any sign of revolt is suicidal; any dreams of independence will be crushed (Porterfield, 29).

So in our dramatic presentation we can imagine these “two processions on a collision course,” as biblical scholar Amy-Jill Levine describes it–Jesus with his followers coming in the sheep’s gate, and Pilate with armed soldiers approaching from the west, (Porterfield, 30). “An altercation was imminent…it would be the confrontation of two competing ideologies, the collision of two incompatible approaches to making and maintaining peace” (Porterfield, 30).

And the city of Jerusalem is important here too. It represents power on so many levels: the political, military might of Rome. The strength of the religious tradition, dominated by the temple, the sacrificial system, the authority of Torah law. The economic power of merchants and money changers who charge exorbitant prices and exchange rates from pilgrims coming to make the required sacrifices at the temple. And social power. Those with wealth and status got positions of authority, while those who were poor in so many ways were marginalized.

The Action

We have talked about characters and props and settings. Now let’s turn our attention to the action, and movements of the characters in this dramatic production. We will want to show the disciples following Jesus’ instructions to procure the donkey. It is such an important symbol. And we should show the response of the crowds around Jesus–the shouting: Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the LORD. A quote from Psalm 118–a Psalm of victory and the last of 6 Psalms used at Passover. These people have freedom and liberation on their minds! And we will want to show the desperate, worried demands from the Pharisees that Jesus rebuke his followers for making “these wild claims” as one translation puts it. “Teacher, get your disciples under control” (Luke 19: 39, The Voice, and the Message). They know the risk of even appearing to challenge Rome, especially with the city so full and so volatile at Passover. Jesus replies that if the people stop shouting, even the stones would cry out (Luke 19:40). In other words, there is a truth here that cannot be suppressed. At the bible study on Wednesday night one of us wondered about showing some close-ups of the disciples’ faces perhaps showing dread, fear, feeling like they had lost control somehow–that this crowd has a momentum that can’t be stopped and is bound to attract unwanted attention.

But it seemed to us that the centrepiece of this scene is Jesus coming into view of the city and weeping. What a dramatic disconnect with the exuberant crowd! The donkey carries a weeping king, as one person expressed it the other evening. One suggestion was to have the stage fall silent and dark, and a lone spotlight trained on Jesus weeping at front and centre stage.

I wonder, is this the one part of his dramatic act that Jesus doesn’t plan for? He is simply overcome with emotions. His lament over the city began days before, when he expressed his dismay over how Jerusalem treats its prophets, and how he longed to gather its children together as a mother hen gathers its chicks under her wings. And now as he comes into view of the city, that lament just pours out of him in a flood of tears.

We wondered, why does he weep? We suspect he weeps because he knows what awaits him if he continues on. He is on a collision course with Roman imperialism. The Pax Romana, the so-called peace of Rome is enforced with cruel brutality, and he will face its full force.

He weeps for the poor, who have been ground down by the systems and structures of power that oppress them.

According to Luke he weeps because so many people have rejected his message and method of peace and salvation. He feels compassion and deep sorrow for the fate of his people, knowing that nationalistic impulses and the desire to violently resist their oppressors will bring down destruction and suffering on the city.

Jason Porterfield, who wrote the book Fight Like Jesus, which we used to frame our Lent series last year, sees this scene of Jesus weeping over Jerusalem as the “interpretive key” to the final week of his life, and that all week he will continue to fight non-violently for peace (Porterfield, 21).

Holy Warrior or Suffering Servant?

Jesus is on a collision course between two incompatible ways of making and maintaining peace. Mary Schertz, in her commentary on the gospel of Luke, contrasts the two ways of working for peace this way. On one hand is the holy warrior, and on the other hand is the suffering servant. Both of these are figures that Jesus knows well from his scripture, his tradition and his peoples’ history. He knows how often they have been threatened, attacked and oppressed and he knows the stories of the heroes who fought back, like Judas Maccabeus, nicknamed The Hammer. Jesus is familiar with the holy warrior image in the old stories–the one who fights alongside God and under God to preserve and protect the people. The warrior and God are partners in delivering judgment and punishment to their enemies who are other nations “out there” who threaten the people. Success is not measured by the size or strength of the fighting force–often they are the underdogs–but is dependent on profound trust in God who saves his people.

Jesus also knows the motif of the suffering servant–a figure that emerges from the prophetic tradition (see Isaiah 42, 49, 50, 52:13-53:12), as one who speaks a message from God that is hard for the people to hear. It is a message that criticizes injustice, rejects false, showy worship, and calls for sincere repentance, and returning to God. And in this case the enemy is not another force “out there,” but rather the sinfulness within their own people. But the prophet, the messenger, suffers for what they say. They are despised and their message is rejected, and they end up absorbing that rejection, even suffering violence on behalf of the people, so that the people might still have time to repent, turn back to God and be saved. This suffering servant is likened to an innocent and helpless lamb.

The hammer and the lamb. The fox and the hen. Which one will Jesus choose to guide his ministry to the very end? Jesus knows both of these, and he wrestles with them during his time of temptation in the wilderness at the beginning of his ministry, and when he prays in the garden before his arrest. His disciples do too–arguing over who will be the greatest in his kingdom, carrying swords to the garden. Here we have two opposing, yet historically compelling options. So which one will Jesus embody?

Surprisingly, Mary Schertz says, neither. At least not completely. Instead, she says that Jesus combines the two. He is a warrior for peace, but he uses non-violent means (Mary Schertz, Believers Church Bible Commentary: Luke, 446). He is a servant of peace, and indeed he suffers, but he is active and direct. He speaks truth to power and calls out evil where he sees it. Like the hen he will be fiercely protective and willing to die for others. He will embody justice, mercy and peace for the most vulnerable, and call others to do the same.

He stages this entry into Jerusalem to imply that he is a king, but not a warrior king. He comes not with coercion, threats and intimidation, but with calls for radical inclusion and extravagant hospitality. He is saviour, liberator, redeemer but not by force. Not with imperial ambitions but with tears of compassion–a weeping king.

A Different Kind of King

Jesus’ street theatre, his dramatic, prophetic living parable, points his people to a different kind of king, but most of them can’t see it, and least not right now. Like so many of the parables in this section of Luke this one leaves us with much to ponder, and our own decision to make. Through this travel section of his gospel, Luke has been setting a choice before us. Jesus has been calling us to a decision about following him. He stands at a crossroads between two competing visions for how to bring about peace, and he invites us to say “yes” and follow him in choosing the way of peace–a peace that comes through justice. A peace that is willing to do the “hard and holy work of confronting empire and all else that diminishes human life…it is the hard and holy work of healing, comforting, releasing possessions, and relinquishing enmity. It is the hard and holy work of choosing another way, one that is nonviolent but also active; a way that is firm and courageous but also compassionate” (Schertz, 446).

We have all the signs on the guidepost now. We know where Jesus is calling us. He is there to show us the way. We know that in all circumstances, in all our experiences, wherever we go, whomever we meet, we are called to seek justice, to offer mercy, to extend hospitality, to build wholeness, work for restoration, and choose peace.

Can this dramatic parable help to sharpen our understanding of Jesus’ way of peace? Can it help us see what is false, misleading and destructive? There will be a couple more dramatic, prophetic events staged by Jesus in holy week. Right after this story Jesus goes to the temple, for what could be called Act 2. He clears the temple of vendors and money changers and the sacrificial animals, declaring the temple a place of prayer for all nations, and not a den of thieves (Luke 19:48). And at the Passover meal with his disciples, he will deepen the symbolism of the bread and wine to represent his broken body and poured out love.

To hold onto the theatre metaphor just a little longer, if we look at current events, we are witnessing no lack of drama in our world–with staged theatrics, symbolic props and quite a cast of characters. We could say we are witnessing the theatre of the absurd. Each day brings a new series of unprecedented actions. But on a more serious note, like the people around Jesus, we don’t necessarily see the things that make for peace either. It is much easier to be suspicious, to name enemies, to stick with like-minded people, to rally nationalistic sentiments, to get our “elbows up”, to double down our own defences out of fear, and to trust no-one. A respected friend who works in the field of peacebuilding feels that we are entering a difficult season for peace makers. As the world order changes, many will not have ears to hear the Prince of Peace.

We Need Holy Week

We are entering Holy Week. This is not an easy week. It is a week for remembering and for lamenting. And in our world today we join Jesus in weeping over so many places.

This is a difficult week. We would much rather jump to next Sunday, to Easter, to resurrection, joy, victory, salvation, flowers and bunnies and new life. We will get there…that is the greatest promise ever made that out of death comes new life, but we need Thursday first–for Jesus to offer us the broken bread and the poured out wine; for Jesus to wash our feet so that we really understand what kind of leader he is. And we need Friday–to hear the false accusations, witness the sham trial, see the mob turning on Jesus, the journey to the cross, the crucifixion so that we recognize the signs and know the power of evil, the strength of lies, the reach of intimidation, the scope of greed for wealth and power, the scale of destruction inflicted by violence, the toll that fear takes on the human psyche, the cost to Jesus of voluntarily absorbing the pain. We do need to sit with the reality of what it is we are capable of as humans. I still find this quote by Aleksandr Sozhenitsyn so powerful: “”The line between good and evil runs not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties — but right through every human heart.” Holy week brings that truth home to us.

And we need Saturday–to wait, exhausted and sorrowful, to prepare the burial spices, the rituals of saying good-bye, to sit by the tomb and weep. We wait in sorrow, but not as those who have no hope. For lament, is after all not despair. Lament is achingly honest and fiercely truthful (real) but it is not hopeless. It leaves space for repentance, for change, for a different choice, and the hope of a restored relationship between the people and God. We need to follow Jesus through his last week, witness his last actions, hear his last words to help us understand what it means to be a non-violent warrior for peace.

We will get to Easter together. We also need the early morning darkness before sunrise. We need to walk to the tomb with the women, carrying spices. We need the shock of the stone rolled away, the empty tomb, the angelic vision. He is not here! He is risen, just like he said! And because of Easter, we will keep working for peace, because being in the peace business means also being in the hope business. So we will keep planting seeds. We will keep working in the cracks. We will keep flowering the cross.